Warm forming of aluminium parts: A way to bridge the gap between aluminium and steel

The effects of temperature on the formability of aluminium sheets in the range of 200-300°C were studied by a number of workers some decades ago, who reported impressive ductility increase, especially on 5xxx alloys, associated with a decrease in work hardening and in strain rate sensitivity. This behaviour can be exploited in order to push back the forming limits of aluminium sheet with a standard stamping process, involving conventional punch and die tooling for mass production (unlike the low volume superplastic processes). The stamping of high-strength alloys becomes possible. The main challenges for warm forming are:

- to find a warm forming lubricant, which ideally requires no extra degreasing step

- to find a suitable thermal design of the process which solves formability problems

- to design a thermally stable process for high-volume production.

To assess the feasibility of such a process for complex parts, a project was launched at Alcan CRV, based on a laboratory deep drawing test part (cross shape) and on a difficult inner door panel. In this study, an organic based lubricant containing small additive particles was found to have acceptable thermal stability for stamping trials up to 350°C. The thermal design of the process is the other key aspect of solving failure issues. In a deep drawing operation, it is generally preferable to have a soft material under the blank holder so that it can be easily drawn. However, the metal in tension on punch or die radius has to transmit the forming loads and distribute the strain to avoid localization. A balance between heated material and non-heated material has to be found to “tailor” the mechanical properties to local stamping difficulties. By heating the blank periphery to 300°C by contact with a heated blank holder while the blank centre remains colder, it is possible to reach the stamping depth without any fracture in the walls. Other forming difficulties come from local embossed areas formed at the end of stamping stroke. It was found that, by heating the neighbouring areas, it was possible to enhance the metal flow close to this forming difficulty. The heated zone must be appropriately positioned, however.

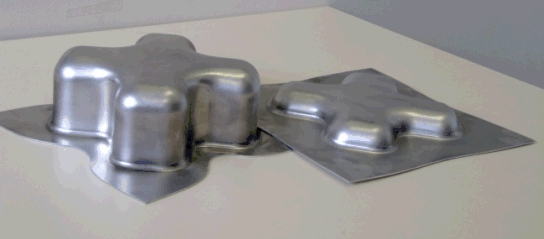

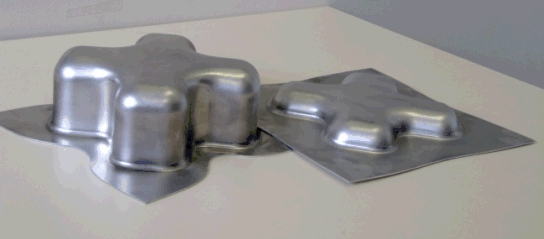

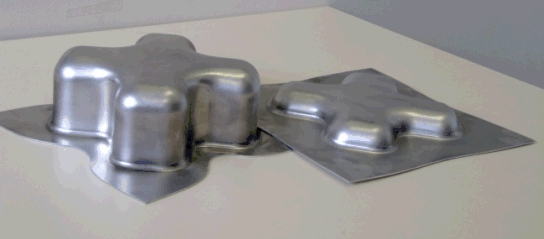

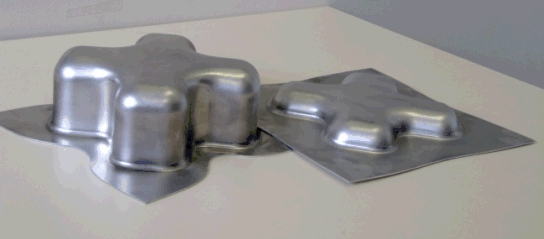

Reproducible high-volume part production was demonstrated by locally pre-heating blanks by contact with heated tools prior to introduction into the stamping press. Issues such as post-stamping operations on semi-warm material, the dimensional accuracy of the warm-formed parts, and process stability over several hours or lubricant compatibility with the rest of the process (degreasing, bonding) still need to be addressed. However, warm forming seems a very relevant process to enable stamping hard aluminium alloys, like those of the 7xxx series, mostly used today for aerospace applications. These Al-Zn-Mg compositions would be able to compete with high-strength steels (also often hot formed) on structural parts such as B-pillars. First results obtained on a low-Cu containing 7xxx alloy, which offers 400 MPa yield strength and is easier to handle in terms of corrosion resistance as well as joining ability than higher strength high-Cu alloys, are very promising, as shown by the illustration below:

Cross-die testing of 3-month old Ultralex™ 7x on Alcan CRV press

Left: Warm forming

Right: Cold forming

Further information: [email protected]

Mise en forme à chaud de flans en aluminium: un moyen de réduire l’écart entre l’aluminium et l’acier

L’effet de la température sur l’aptitude à la mise en forme des tôles en aluminium dans la gamme de 200 - 300 °C a été étudié par plusieurs métallurgistes depuis plusieurs décennies. Ils ont constaté une augmentation spectaculaire de la ductilité, particulièrement sur les alliages aluminium – magnésium de la famille 5000, associée à une diminution de l’écrouissage et de la sensibilité à la vitesse de déformation.

Ce comportement peut être exploité pour repousser les limites de l’aptitude à la mise en forme des tôles en aluminium par emboutissage avec un outillage classique pour des productions de grande série (à la différence des productions de faibles volumes par déformation superplastique).

L’emboutissage des alliages d’aluminium à haute résistance devient possible.

Les principales difficultés à surmonter pour la mise en forme à chaud sont de:

- disposer d’un lubrifiant pour mise en forme à chaud, qui n’impose pas de dégraissage ultérieur,

- trouver une gamme de traitements thermiques qui résout les problèmes de formabilité

- adapter cette gamme à une production de grande série.

Pour évaluer la faisabilité d’un tel mode opératoire sur des pièces complexes, telles d’un panneau intérieur de portière, un projet a été lancé par Alcan CRV. Les essais de laboratoire consistent à tester des éprouvettes d’emboutissage profond en croix.

Pour cette étude, on disposait d’un lubrifiant organique contenant de fines particules comme additif. Il s’est révélé stable jusqu’à 350 °C lors des essais d’emboutissage.

La gamme des traitements thermiques est l’autre clé pour résoudre les problèmes de rupture. Dans une opération d’emboutissage profond, il est généralement préférable d’avoir un matériau adouci dans le serre flanc de manière à ce qu’il soit facilement étiré.

Toutefois, le métal en tension sous le poinçon ou dans le rayon de matrice doit transmettre les forces de mise en forme et répartir les contraintes pour éviter des concentrations localisées.

Il faut donc trouver un compromis entre l’état recuit et l’état écroui pour avoir des propriétés mécaniques sur mesure, adaptées aux difficultés localisées d’emboutissage.

En chauffant la périphérie des flancs à 300 °C en le mettant en contact avec un flanc support chaud, tandis que le centre du flanc reste plus froid, il est alors possible d’atteindre la profondeur nominale d’emboutissage sans rupture sur les parois latérales.

Les zones plissées en fin de course de l’outillage constituent une autre difficulté qu’il est possible de résorber en améliorant l’écoulement du métal dans ces zones. Il faut cependant bien positionner le chauffage.

Il a été prouvé qu’il est possible d’appliquer cette méthode à une production de grande série. Elle consiste à préchauffer localement des flancs, avant leur introduction dans la presse d’emboutissage, par contact avec des tôles chauffées.

Les questions relatives aux opérations de parachèvement après emboutissage sur des ébauches encore tièdes, la précision dimensionnelle des pièces formées à chaud, et la stabilité du processus pendant plusieurs heures ou la compatibilité des lubrifiants avec la suite de la gamme de fabrication (dégraissage, collage) ont encore besoin d’être affinées.

Cependant, la mise en forme à chaud semble être un processus approprié pour améliorer l’aptitude à l’emboutissage des alliages d’aluminium à haute résistance, comme ceux de la série 7000, de plus en plus utilisés aujourd’hui dans les applications aérospatiales.

Ces alliages Al-Mg-Zn devraient être en mesure de compléter avec les aciers à haute limite d’élasticité (mis aussi en forme à chaud) dans les pièces structurales telles que les montants-B.

Les premiers résultats obtenus avec des 7000 à bas cuivre dont:

- la limite d’élasticité est de 400 MPa,

- la tenue à la corrosion est plus facile à contrôler que celle des 7000 plus chargés en cuivre,

- l’aptitude à l’assemblage (soudage) est meilleure que celle des 7000 plus chargés en cuivre,

montrent que ces alliages sont prometteurs ainsi que l’illustre la figure ci-après.

Alliage UltralexTM 7x – maturation 3 mois

Essai Eprouvette en croix à CRV Alcan

A gauche : mise en forme à chaud, à droite mise en forme à froid.

Pour plus d’information: [email protected]

Die Warmumformung von Aluminiumteilen: Ein Weg, die Lücke zwischen Stahl und Aluminium zu schliessen

Der Einfluss der Temperatur auf das Umformverhalten von Aluminiumblechen im Bereich von 200-300°C wurde durch eine Vielzahl von Studien schon einige Jahrzehnte zurück aufgezeigt. Dabei wurden signifikante Steigerungen der Dehnbarkeit, speziell bei 5000er Legierungen, zusammen mit einer Abnahme der Kaltverfestigung und der Dehngeschwindigkeits-Empfindlichkeit festgestellt. Dieses Verhalten kann ausgenutzt werden, um die Grenzen der Umformfähigkeit von Aluminiumblechen in Standardprozessen bei Verwendung konventioneller Werkzeuge in der Massenfertigung (also nicht wie beim Superformen mit kleinen Stückzahlen) deutlich auszuweiten. Das Pressen hochfester Legierungen konnte hiermit ermöglicht werden. Die wesentlichen Herausforderungen beim Warmumformen sind:

- Ein für die Warmumformung geeignetes Schmiermittel zu finden, welches idealerweise keine zusätzliche Entfettung benötigt

- Ein geeignetes Temperatur- Setup zu finden, welches die Umformprobleme löst

- Einen thermisch stabilen Prozess zu entwickeln, der für eine Massenfertigung geeignet ist

Um die Machbarkeit eines solchen Prozesses für ein komplexes Bauteil zu prüfen, wurde bei Alcan CRV ein Projekt basierend auf Labor- Tiefziehversuchen und einem schwierig zu formenden Tür- Innen- Panel gestartet. In dieser Studie wurde herausgefunden, dass ein organisches Tiefzieh- Schmiermittel mit sehr kleinen Additiv- Partikeln eine akzeptable thermische Stabilität für Tiefziehversuche bis 350°C besitzt. Die thermische Auslegung des Prozesses war ein anderer Schlüsselaspekt, um Ursachen für ein mögliches Versagen des Prozesses zu beseitigen. In einem Tiefziehprozess ist es generell von Vorteil, unter dem Niederhalter ein weiches Material zu haben, welches sich leicht tiefziehen lässt. Dabei muss das Material gerade an den Werkzeugradien und am Kolben die Umformkräfte übertragen und die Spannungen zur Vermeidung lokaler Spannungsspitzen möglichst gleichmäßig verteilen. Ein Gleichgewicht zwischen erwärmtem und nicht erwärmtem Material musste gefunden werden, um die mechanischen Eigenschaften den jeweiligen Umformbedingungen anzupassen. Das Erwärmen des Bleches im Außenbereich auf bis zu 300°C mit Hilfe eines aufgeheizten Blech- Niederhalters, bei gleichzeitigem Verbleib des Blech- Mittenbereiches bei niedrigerer Temperatur, ermöglicht dabei die nötige Tiefziehtiefe ohne Risse des Bleches.

Andere Umformprobleme entstanden an lokalen gestanzten Bereichen am Ende des Tiefzieh- Hubs. Es konnte festgestellt werden, dass durch das Aufheizen benachbarter Bereiche der Metallfluss im Bereich dieser Umformprobleme verbessert werden konnte. In jedem Fall musste auf eine gute Positionierung der aufgeheizten Zone geachtet werden.

Eine reproduzierbare Fertigung hoher Stückzahlen mit Hilfe von Blechen, die durch den Kontakt mit aufgeheizten Werkzeugen vor dem Tiefziehen erwärmt wurden, konnte nachgewiesen werden.

Weitere Themen, wie z.B. dem Tiefziehen nachgeschaltete Verarbeitungsschritte auf halbwarmen Material, der dimensionalen Genauigkeit von warmumgeformten Material oder der Prozesssicherheit über mehrere Stunden und der Kompatibilität des Schmiermittels mit dem Rest des Prozesses (Entfetten, Fügen) müssen noch genauer untersucht werden. Dennoch scheint das Warmumformen eine relevante Möglichkeit, das Tiefziehen hochfester Aluminiumlegierungen, wie z.B. den 7000er- Legierungen im Flugzeugbau, zu ermöglichen. Diese Al-Zn-Mg Legierungen könnten mit hochfesten Stählen (oft auch warmumgeformt) zum Beispiel bei B- Säulen konkurrieren. Erste Versuche mit einer 7xxx- Legierung mit niedrigem Cu- Gehalt, welche eine Dehngrenze von 400 MPa aufweist und dabei korrosionsunkritischer als eine Legierung mit höherem Cu- Gehalt ist, zeigen wie im Bild unten vielversprechende Ergebnisse:

Tiefziehversuch an einer 3 Monate alten UltralexTM 7x Probe in

einer Alcan CRV Presse.

Links: Warmumformen Rechts: Kaltumformen

Weitere Informationen unter: [email protected]

Stampaggio a semicaldo di parti in alluminio: un modo per ridurre le differenze tra alluminio ed acciaio

Qualche decennio fa, un gruppo di operatori studiò gli effetti della temperatura sulla lavorabilità delle lamiere di alluminio entro un intervallo di temperature compreso tra 200 e 300 °C; tali studi hanno evidenziato un fortissimo incremento della duttilità, specialmente per le leghe di tipo 5xxx, associato ad una riduzione dell’incrudimento e della sensibilità allo strain rate (velocità di deformazione). Tale comportamento può essere sfruttato per ridurre i limiti di formatura delle lamiere di alluminio con un procedimento di stampaggio standard, che comporti l’utilizzo di normali utensili di stampaggio per la produzione di massa (diversamente dai processi superplastici a basso volume). Diviene così possibile lo stampaggio di leghe ad alta resistenza. Le principali sfide dello stampaggio a caldo sono le seguenti:

- individuare un lubrificante che non necessiti di ulteriori passaggi di sgrassaggio;

- mettere a punto un’adeguata configurazione termica del processo che risolva i problemi di formabilità;

- configurare un processo termicamente stabile per la produzione di grandi volumi.

Per valutare la fattibilità di un tale processo con parti complesse, è stato lanciato presso la Alcan CRV un progetto basato su un test di imbutitura condotto in laboratorio (forma trasversale) e su un difficile pannello interno di portiera. In tale studio, si è scoperto che un lubrificante a base organica contenente piccole particelle di additivo aveva una stabilità termica sufficiente per effettuare degli stampaggi di prova sino ad una temperatura di 350 °C. La configurazione termica del processo è un altro aspetto di fondamentale importanza per risolvere i problemi di rotture. Di solito nel processo di imbutitura si preferisce avere del materiale tenero sotto il premilamiera, così da facilitare l’imbutitura. Tuttavia, il metallo in tensione sul raggio dello stampo deve trasmettere i carichi di formatura e distribuire la deformazione per evitare la localizzazione della stessa. E’ necessario trovare un equilibrio tra il materiale riscaldato e quello non riscaldato per “adattare su misura” le proprietà meccaniche alle specifiche problematiche di stampaggio. Riscaldando la periferia dell’elemento tranciato a 300 °C tramite contatto con un premilamiera riscaldato e mantenendo il centro del tranciato più freddo, è possibile ottenere la profondità di stampaggio desiderata senza provocare fratture nelle pareti. Altri problemi di formatura possono insorgere nelle aree localmente a rilievo che si formano alla fine della corsa di stampaggio. Si è scoperto che, riscaldando le aree circostanti, era possibile potenziare il flusso di metallo in prossimità di questo punto difficile. Tuttavia, è necessario che la zona riscaldata venga posizionata adeguatamente.

La possibilità di ottenere in maniera riproducibile grandi volumi di pezzi è stata dimostrata pre-riscaldando localmente gli elementi tranciati tramite contatto con utensili riscaldati prima dell’introduzione nella pressa di stampaggio. Devono ancora essere affrontate diverse problematiche riguardanti le operazioni post-stampaggio sul materiale semi-caldo, la precisione dimensionale delle parti stampate a semicaldo, la stabilità del processo su un arco temporale di diverse ore o la compatibilità del lubrificante con il resto del processo (sgrassaggio e fissaggio). Tuttavia, lo stampaggio a semicaldo sembra essere un processo molto rilevante per consentire la formatura di leghe di allumino dure, quali quelle della serie 7xxx, attualmente utilizzate soprattutto nelle applicazioni aerospaziali. Queste composizioni Al-Zn-Mg potrebbero competere con gli acciai ad alta resistenza (anch’essi spesso termoformati) per l’applicazione in parti strutturali quali le colonne a B. I primi risultati ottenuti su una lega 7xxx a basso contenuto di Cu, che offre una resistenza alla rottura di 400 MPa ed è più facile da gestire in termini di resistenza alla corrosione nonché di capacità di congiunzione rispetto alle leghe a maggior tenore di Cu, sono molto promettenti, come dimostra la seguente figura:

Test condotto su Ultralex™ 7x di tre mesi su pressa Alcan CRV

A sinistra: stampaggio a semicaldo

A destra: stampaggio a freddo

Per ulteriori informazioni: [email protected]